History

History of Buddhism

The history of Buddhism spans from the 5th century BCE to the present; which arose in the eastern part of Ancient India, in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhārtha Gautama. This makes it one of the oldest religions practiced today. The religion evolved as it spread from the northeastern region of the Indian subcontinent through Central, East, and Southeast Asia. At one time or another, it influenced most of the Asian continent. The history of Buddhism is also characterized by the development of numerous movements, schisms, and schools, among them the Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna traditions, with contrasting periods of expansion and retreat.

Life of the Buddha

Siddhārtha Gautama was the historical founder of Buddhism. He was born a Kshatriya warrior prince in Lumbini, Shakya Republic, which was part of the Kosala realm of ancient India.He is also known as the Shakyamuni (literally: "The sage of the Shakya clan").

After an early life of luxury under the protection of his father, Śuddhodhana, the ruler of Kapilavasthu which later became incorporated into the state of Magadha, Siddhartha entered into contact with the realities of the world and concluded that life was inescapably bound up with suffering and sorrow. Siddhartha renounced his meaningless life of luxury to become an ascetic. He ultimately decided that asceticism couldn't end suffering, and instead chose a middle way, a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-indulgence and self-mortification.

Under a fig tree, now known as the Bodhi tree, he vowed never to leave the position until he found Truth. At the age of 35, he attained Enlightenment. He was then known as Gautama Buddha, or simply "The Buddha", which means "the enlightened one", or "the awakened one".

For the remaining 45 years of his life, he traveled the Gangetic Plain of central India (the region of the Ganges/Ganga river and its tributaries), teaching his doctrine and discipline to a diverse range of people. By the time of his death, he had thousands of followers.

The Buddha's reluctance to name a successor or to formalise his doctrine led to the emergence of many movements during the next 400 years: first the schools of Nikaya Buddhism, of which only Theravada remains today, and then the formation of Mahayana, and Vajrayana, pan-Buddhist sects based on the acceptance of new scriptures and the revision of older techniques.

Followers of Buddhism, called Buddhists in English, referred to themselves as Sakyan-s or Sakyabhiksu in ancient India. Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez asserts they also used the term Buddha, although scholar Richard Cohen asserts that that term was used only by outsiders to describe Buddhists.

Early Buddhism:

Early Buddhism remained centered on the Ganges valley, spreading gradually from its ancient heartland. The canonical sources record two councils, where the monastic Sangha established the textual collections based on the Buddha's teachings and settled certain disciplinary problems within the community.

1st Buddhist council (5th century BC)

The first Buddhist council was held just after Buddha's Parinirvana and presided over by Gupta Mahākāśyapa, one of His most senior disciples, at Rājagṛha (today's Rajgir) during the 5th century under the noble support of king Ajāthaśatru. The objective of the council was to record all of Buddha's teachings into the doctrinal teachings (sutra) and Abhidhamma and to codify the monastic rules (Vinaya). Ānanda, one of the Buddha's main disciples and his cousin, was called upon to recite the discourses and Abhidhamma of the Buddha, and Upali, another disciple, recited the rules of the Vinaya. These became the basis of the Tripiṭaka (Three Baskets), which is preserved only in Pāli.

The Mauryan Emperor Aśoka (273–232 BC) converted to Buddhism after his bloody conquest of the territory of Kalinga (modern Odisha) in eastern India during the Kalinga War. Regretting the horrors and misery brought about by the conflict, the king magnanimously decided to renounce violence, to replace the misery caused by war with respect and dignity for all humanity. He propagated the faith by building stupas and pillars urging, amongst other things, respect of all animal life and enjoining people to follow the Dharma. Perhaps the finest example of these is the Great Stupa of Sanchi, (near Bhopal, India). It was constructed in the 3rd century BC and later enlarged. Its carved gates, called toranas, are considered among the finest examples of Buddhist art in India. He also built roads, hospitals, resthouses, universities and irrigation systems around the country. He treated his subjects as equals regardless of their religion, politics or caste.

This period marks the first spread of Buddhism beyond India to other countries. According to the plates and pillars left by Aśoka (the edicts of Aśoka), emissaries were sent to various countries in order to spread Buddhism, as far south as Sri Lanka and as far west as the Greek kingdoms, in particular the neighboring Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, and possibly even farther to the Mediterranean.

3rd Buddhist council (c. 250 BC)

King Aśoka convened the third Buddhist council around 250 BC at Pataliputra (today's Patna). It was held by the monk Moggaliputtatissa. The objective of the council was to purify the Saṅgha, particularly from non-Buddhist ascetics who had been attracted by the royal patronage. Following the council, Buddhist missionaries were dispatched throughout the known world.

Hellenistic world

Some of the edicts of Aśoka describe the efforts made by him to propagate the Buddhist faith throughout the Hellenistic world, which at that time formed an uninterrupted continuum from the borders of India to Greece. The edicts indicate a clear understanding of the political organization in Hellenistic territories: the names and locations of the main Greek monarchs of the time are identified, and they are claimed as recipients of Buddhist proselytism: Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid Kingdom (261–246 BC), Ptolemy II Philadelphos of Egypt (285–247 BC), Antigonus Gonatas of Macedonia (276–239 BC), Magas (288–258 BC) in Cyrenaica (modern Libya), and Alexander II (272–255 BC) in Epirus (modern Northwestern Greece).

- "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka)." (Edicts of Aśoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika).

Furthermore, according to Pāli sources, some of Aśoka's emissaries were Greek Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures:

- "When the thera (elder) Moggaliputta, the illuminator of the religion of the Conqueror (Aśoka), had brought the (third) council to an end (...) he sent forth theras, one here and one there: (...) and to Aparantaka (the "Western countries" corresponding to Gujarat and Sindh) he sent the Greek (Yona) named Dhammarakkhita". (Mahavamsa XII).

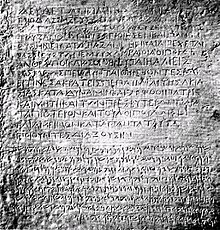

Aśoka also issued edicts in the Greek language as well as in Aramaic. One of them, found in Kandahar, advocates the adoption of "piety" (using the Greek term eusebeia for Dharma) to the Greek community:

- "Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King Piodasses (Aśoka) made known (the doctrine of) piety (Greek:εὐσέβεια, eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made men more pious, and everything thrives throughout the whole world."

- (Trans. from the Greek original by G.P. Carratelli[6])

It is not clear how much these interactions may have been influential, but some authors[citation needed] have commented that some level of syncretism between Hellenist thought and Buddhism may have started in Hellenic lands at that time. They have pointed to the presence of Buddhist communities in the Hellenistic world around that period, in particular in Alexandria (mentioned by Clement of Alexandria), and to the pre-Christian monastic order of the Therapeutae (possibly a deformation of the Pāli word "Theravāda"), who may have "almost entirely drawn (its) inspiration from the teaching and practices of Buddhist asceticism" and may even have been descendants of Aśoka's emissaries to the West. The philosopher Hegesias of Cyrene, from the city of Cyrene where Magas of Cyrene ruled, is sometimes thought to have been influenced by the teachings of Aśoka's Buddhist missionaries.

Buddhist gravestones from the Ptolemaic period have also been found in Alexandria, decorated with depictions of the Dharma wheel. The presence of Buddhists in Alexandria has even drawn the conclusion: "It was later in this very place that some of the most active centers of Christianity were established".

In the 2nd century AD, the Christian dogmatist, Clement of Alexandria recognized Bactrian Buddhists (śramanas) and Indian gymnosophistsfor their influence on Greek thought:

- "Thus philosophy, a thing of the highest utility, flourished in antiquity among the barbarians, shedding its light over the nations. And afterwards it came to Greece. First in its ranks were the prophets of the Egyptians; and the Chaldeans among the Assyrians; and the Druids among the Gauls; and the śramanas among the Bactrians ("Σαρμαναίοι Βάκτρων"); and the philosophers of the Celts; and the Magi of the Persians, who foretold the Saviour's birth, and came into the land of Judea guided by a star. The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called śramanas("Σαρμάναι"), and others Brahmins ("Βραφμαναι")." Clement of Alexandria "The Stromata, or Miscellanies" Book I, Chapter XV